What Smartphone Nation Teaches Us About Approaching Life in a Data-Driven World

By: Meghan Voll

The start of the new year has had me thinking a lot about the word redress in the context of digital technologies and age. My research on the Data Harms in Canada: Investigating the Significance of Age Project at the Starling Centre has focused quite a bit on redress in the last year. We’ve been working on creating knowledge mobilization initiatives aimed at empowering younger and older adults with the tools to protect themselves against the negative impacts caused by digital technologies, such as misinformation. However, I’ve also been thinking about redress as it has crept into the nuances of my social—and technological—life. At Christmas, my niece and nephew made their first real steps into more serious uses of digital technologies, such as texting and messaging online. It’s not uncommon that I receive a silly text message or video from them every other day now. Around this time, I also found myself reviewing my Year in Booksresults on GoodReads (I read enough pages to wrap around the pyramids of Giza) and focusing on a particular title I had all but forgotten reading. This was Smartphone Nation by Dr. Kaitlyn Regehr.

This book was so memorable because it was one of the few resources aimed at individuals and families with young children that provides clear methods and tools for redress against the risks posed by digital technologies. I am surprised that more people do not know about this book, and that few other resources like it have been released since its publication in 2025. Smartphone Nation encourages a need for a digital education that makes it required reading for anyone unsure about their technological health. In the same way that our elementary and high schools teach health or physical education,Smartphone Nation encourages its readers to implement healthy technology use similar to developing good nutrition habits. It is this text’s approach to the use of digital technologies in everyday life that makes it so refreshing and accessible to read. Smartphone Nation encourages its readers to approach the choice to use a particular technology as if it comes with a digital nutrition label. Readers will learn how to identify particular risks that enable them to better understand whether a particular technology is risky, and step back if they are becoming too reliant on them.

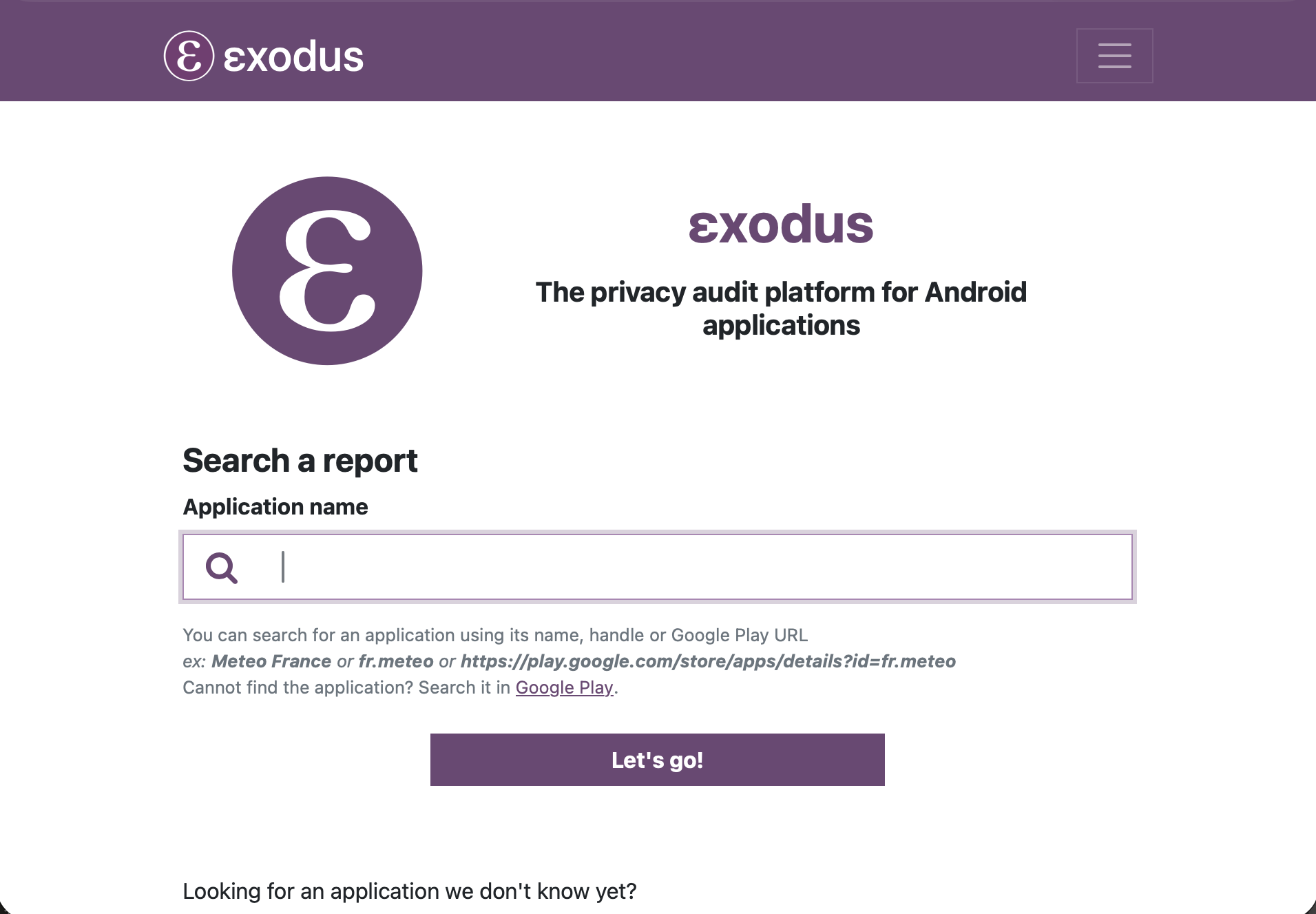

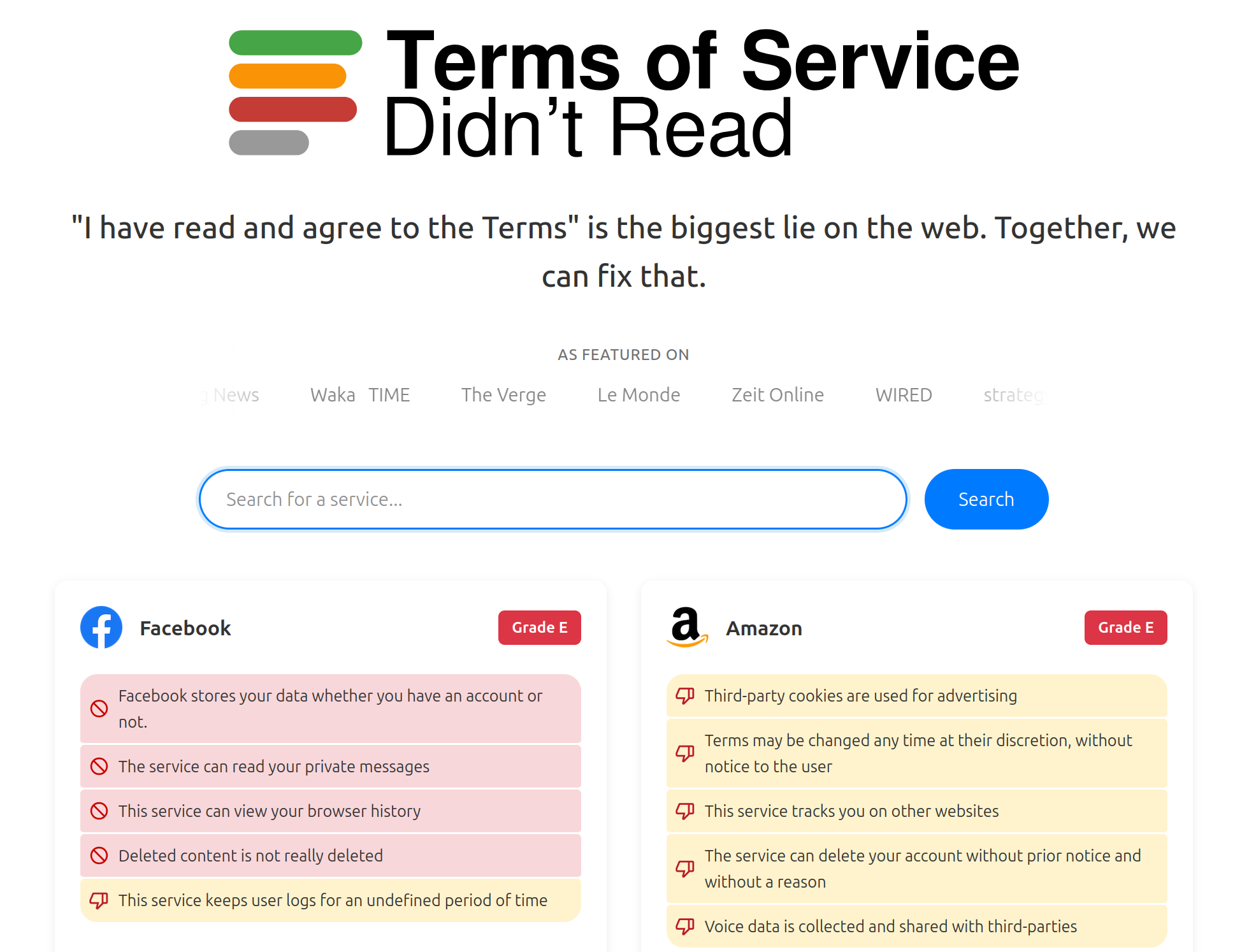

What makes Smartphone Nation required reading for anyone—individuals or parents alike—is the digestible and feasible tools offered to mitigate the risks associated with digital technologies. Three examples come to mind that I hope convince the avid reader to pick up a copy of this book at their local library or bookstore. The first of these examples are the clear and easy-to-use tools offered by the book, such as Terms of Service, Didn’t Read. I’m always looking for new and publicly accessible tools to inform me about the risks my data could be exposed to when I’m deciding whether to sign up for a new social media platform or website. As a data harms scholar, I often look for tools that do not require reading lengthy privacy policies, terms of service agreements, and are geared towards public use. Since I’m on the topic, I’ll recommend some of my other favourite tools besides Terms of Service, Didn’t Read, namely Exodus Privacy.

Terms of Service, Didn’t Read has become a fan favourite in my home when we want to know more about the platforms we’re using, and the data we’re sharing. Put simply, you can input the name of a social media platform (e.g. Instagram, Facebook, etc.) that you might be curious about. The site will grade the platform’s data sharing practices, such as A+ (excellent) or F (terrible), and list the kinds of uses your data may be at-risk for in plain language. It is my opinion that the introduction of these tools by Smartphone Nation provides readers a vocabulary to interpret the digital nutrition labels of their favourite platforms, and make more informed choices about how they use such platforms.

The second example from Smartphone Nation that makes it required reading for anyone interested in their technological health is the methods—or practices—it recommends. I mentioned earlier that our schools equip us with education pertaining to our health, physical, and even sexual wellbeing, but not our digital wellbeing.Smartphone Nation provides several educative techniques to self-assess digital wellbeing and spot signs of unhealthy uses of digital technologies. A very simple practice that the book suggests is digital “spring cleaning”. This practice encourages individuals to regularly review the feeds of the social media platforms they use the most, and delete or unfollow the accounts that no longer inspire or educate them. Similarly, another practice this book suggests is to regularly review and update passwords to reduce the risk of being compromised or hacked. Here, I am reminded of how timely these practices could be implemented, since it is the New Year’s season (or tail end of it), although it is up to the reader how often they do a digital “spring-clean”.

Here, Smartphone Nation also equips the reader with several methods to determine what can be “cleaned” or “kept” if using these practices. One such example of these methods is the “walkthrough method” the book introduces. Similar to the idea of digital spring-cleaning, readers are encouraged to go through the social media platforms (or websites) they use the most and reflect on how the content they see makes them feel. If the reader consistently finds themselves feeling negatively or craving a dopamine hit from the content they see, this could be a sign of unhealthy use that requires either stepping away or “recalibrating” their personal algorithms. The idea of reflection and awareness is another reason I found this book so important and insightful. As much as we advocate, Big Tech has never been the first to take accountability for the dangers they put their users at risk for, whether through the exchange of data, the addictive design features they create, or the content they allow to be seen. It is up to us—the users—to protect ourselves, and those we care about. Smartphone Nation does not try to argue the injustice or unfairness of this situation (although it does talk about it). Instead, the book acknowledges this situation to devise methods that allow us to take back some control over the content we consume and the data we provide to Big Tech companies.

A final example of why this book should be required reading is for its focus on families and children living in a data-driven world, such as my niece and nephew. In particular, Smartphone Nation provides parents with methods to talk about digital health with their children and create safe spaces to talk about unsafe use and content. For example, the book encourages readers to think about and create a space for better quality screen time. This approach implores parents to be a part of the screen time their children enjoy, such as by watching a television show or YouTube videos together, so as to provide a safe space for their children to feel comfortable talking about the content (good or bad) that they consume. Of course, these methods are not the full solution to the major harms, emergent or existent, posed by use of digital technologies (and AI) by young people and children. However, they provide a critical start to at-home prevention.

As a verb, the term redress refers to a “remedy or ability to set right (an undesirable or unfair situation)”. I believe that Smartphone Nation by Dr. Kaitlyn Regehr provides the methods and tools for this in abundance, and I hope to find many more resources like this book this year. While this is my first blog post with the Starling Centre, I hope to make these data harms book blog posts a regular occurrence—a GoodReads for your digital health, if you will. Until then, I hope you will consider borrowing this text from your local library and reading it as you are able. I can say you will not be disappointed!

Author Info:

Meghan Voll

Ph.D. Candidate | Research Assistant

Data Harms & Aging in Canada Project

Affiliated with The Starling Centre