“Fauxtomation”

By: Daniel Nunez

The hype and increased prevalence of Artificial Intelligence companies and their products have renewed public anxieties about automation. There is understandable public fear that Artificial Intelligence, chatbots, image recognition algorithms, and robotics represent an incoming wave of digital and mechanical labourers that will replace human workers. In speaking with community members at our ongoing Glassroom Exhibition that showcases the history of labour movements against tech corporations, I heard the fears of automation acutely, especially as these corporations are gleefully adopting thus human-replacement narrative to bolster their technologies utility and power.

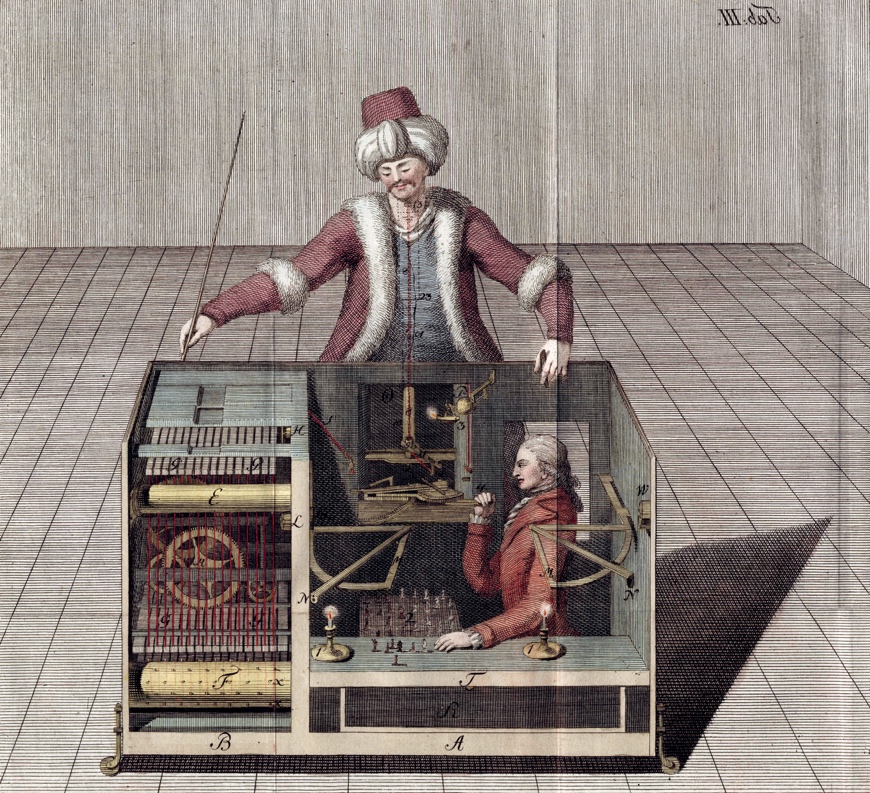

But there is another story about automation that we can tell, a story of how a life-sized, mechanical chess player still reminds as that automation often acts as a smoke-screen, a technological spectacle that obscures the real human labour that technological systems keep out of sight.

The Mechanical Turk, the famed eighteenth century automaton created by Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1770, was equally celebrated as it was puzzling. Kempelen claimed that his machine was capable of automated thought, playing each game of chess by deciding is moves for itself and moving them across the board, nearly 200 years before the earliest IBM computers were capable of playing chess. Like many of its computer counterparts, the Mechanical Turk won most of its game, famously beating celebrity chess enthusiasts like Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin.

Though the Mechanical Turk was celebrated for its capabilities and theatrics, it was widely considered to be a hoax. Many hypothesized that there was a human hidden in its cabinet, though its small size required that the hidden player must have been a child, dwarf, or double-leg amputee. But the secret mechanics of the Mechanical Turk were never discovered, and the true identity of its hidden chess master lost to history.

Today, a quick search of the Mechanical Turk yields another technological system that “hides” human labour: Amazon’s Mechanical Turk or MTurk platform. Launched in 2005, MTurk is a microwork platform where companies and research groups hire piecemeal labour called “Human Intelligence Tasks” such as data labelling, transcribing audio, writing descriptions for video content, and more, to patch gaps and train programs for extremely low pay. This “artificial artificial intelligence” often represents the actual labour behind the “learning abilities” of AI systems, and companies have used MTurk to train their AI products, while exploiting the system to acquire finished tasks while denying users the small amounts of payment promised.

In a comparative analysis, Dr. Elizabeth Stephens argues that thinking with the historic Mechanical Turk and Amazon’s MTurk allows us the ways that technological systems deflect attention away from the economic exploitation that powers the technical underpinnings of automation. MTurk represents a misdirection, one that does not entirely mask the apparent fact that machine learning requires repetitive cognitive labour to train programs, but rather hides the exploitative conditions in which that labour is performed.

The story of automation thus, should not only prompt us to think about what work will be replaced by machines. We must also think of the ways that machines are increasingly hiding humans within their mechanical and digital systems, the invisible workers who are hidden under the guise of automation to removal harmful content from AI systems or social media. These are just a fraction of the stories, the lives of workers across the globe that require our solidarity and support. When I think of the Mechanical Turk, I think of who entertained masses of onlookers might have, who sparred with famed statesman and intellectuals, hidden by the spectacle of an automaton. I think of the spectacle of Tesla’s Optimus “advanced” GrokAI powered robots who were actually controlled by Tesla workers remotely. The fear of robotic or AI overtaking our work in society cannot alone operate as a critique of these systems. We need to ensure that the labour required to create these spectacles is not lost to history. The fight against the exploitation of unseen data workers and platform requires that we continue to tell their stories.

Featured image

The Mechanical Turk. Illustrated by

Joseph Friedrich Freiherr von Racknit

. Wikipedia