The Fantasy of AI Therapy

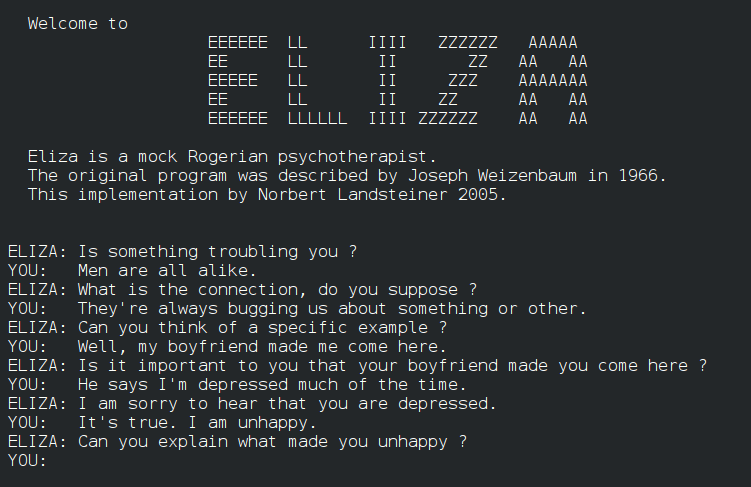

The development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the mid-20th century has been long intertwined with fantasies of computer therapists. Joseph Weizenbaum created ELIZA, one of the first chatbots, to explore communication between humans and computers. Against his own expectations and intentions, Weizenbaum was surprised to learn that users enjoyed discussing personal matters with ELIZA’s “DOCTOR” script, an automated set of responses that mimicked the recursive questions of a Rogerian psychotherapist.

Weizenbaum made ELIZA a mock-therapist to circumvent its limited key-word recognition capabilities, allowing “her” to continue to prompt responses with open-ended questions. But despite Weizenbaum’s disapproval, ELIZA would inspire generations of technologies aiming to harness computers in the automation of mental health care.

Today, the recognition and increased acceptance of the growing need for the expansion of mental health care services across Canada, coupled with the detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, have raised both public interest, and millions of dollars in investment for the development of mental health care platforms. In more recent years these platforms have been trialed in public health units. A recently concluded trial aimed to support staff in the Northhamptomshire National health with the AI mental health service Wysa, designates a potential growth in adoption from both public health units, and workplaces to address the 79% of employees who reported that they previously considered quitting their positions.

While coverage from popular new outlets have highlighted troubling and potentially traumatic failures to recognize users reporting assault and sexual abuse, this coverage often fails to trouble the assumption that these services are performing therapy in the first place. While both Woebot and Wysa have attempted to clarify that their services can not adequately support users experiencing abuse, this over-assignment of the capabilities of services that market themselves as “AI Mental Health Services” continues to benefit from the hype and framing of AI as a one-size-fits-all solution for addressing complex social issues.

Both Woebot Health and Wysa, two among the longest standing and heavily researched services primarily rely on natural language processing recognition to appropriately connect users to a limited collection of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) exercises.

Hannah Zeavin, historian of both the psychological sciences and technology, argues that the development of CBT in the late twentieth century coincides with increasing interest in computer-based automation of mental health care services. Even in these early experiments with computer therapies, Zeavin identifies that CBT’s objective to re-train and, in a sense, “automate” the rejection out of negative thought patterns synergized well with these early efforts, and continues to underpin most automated mental health care platforms today. Automation as a concept itself, has become a dominant definition of both how the mind works, and of how therapy ought to work.

The trouble with this shift is not that the traditional dyad between human therapist and patient has been undermined by the third party of technology. As she argues in The Distance Cure: A History of Teletherapy, therapy has always had a triadic: patient, therapist and the medium of communication. But, human-machine therapies have always suggested and hoped, that the human therapist is extrinsic.

Collapsing the nuances between traditional patient-centered therapeutic practices, psychoanalysis, and culturally sensitive therapies, particularly those that draw from non-Western healing practices can not be automated. Part of the question that we should be asking about the continued push for automation should also ask what kinds of care workers are continuously frame as superfluous to the practices of therapy, especially as that work is historically associated with women. This too is one of the unintended legacies of ELIZA.

While it is important that critical data scholars continue to question the efficacy and safety of mobile mental health services, it is crucial that we consider the role automation in mental health continues to undermine the quality of life afforded to critical care workers. The truth may be that many of the problems associated with equitable access to mental health cannot just be understood solely as a public health, but one that centers the dignity of both patients and care providers.

Featured Image

Wikipedia, ELIZAconversation.jpg. Public Domain